Two days ago I started this 3-part series by defining categories of difficult students. As I said in that piece, my classrooms rarely have any challenging students; my secret is stopping the behavior before it starts.

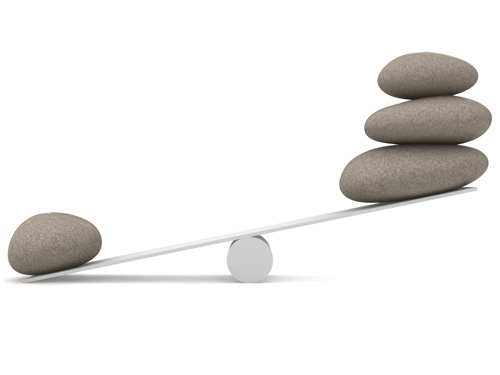

Another way to think about it is

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” — Benjamin Franklin

Adult students rarely (if ever) have a goal of being the most difficult in class. They become challenging as they start exhibiting certain behaviors, often unconsciously in response to a variety of circumstances. Classroom management for adults doesn’t have to be a challenge; by creating an environment from the beginning where those behaviors are not tolerated, they just don’t appear as often.

I teach adults in a variety of circumstances and “classroom” settings from small groups to large conventions, and even out on the ski slopes. Because the environments and learning requirements are different, I don’t necessarily use all of these techniques every time I teach. But I assure you that I use them all consistently in adult learner environments.

Establish your authority from the beginning of class. This may seem obvious or implied, but it is not. A phrase I commonly use is “own the class.” An easy method for doing this is to begin by establishing some rules. The person who makes the rules is the person in charge. These rules can cover any range of topics, such as cell phone etiquette, forbidding negative self-talk, safely using equipment, how questions will be asked or any other thing that could use a rule. A couple rules is all you need (unless you actually “need” more).

Why this works: We are conditioned to follow, listen and obey authority figures. By establishing authority from the beginning, most students will not question or challenge it. It also sets the stage for correcting individuals as necessary. This is particularly effective in managing the Take Over student, since their behavior is usually a result of feeling like no one is in charge of the group.

Verify minimum requirements. Not all classes require a set of skills or knowledge prior to taking the class. If the class does, do not assume all students will meet those minimums unless a formal method of tracking is in place. Instead, use pre-work (something to be completed prior to arriving to class) or an initial exercise immediately after class begins to verify baseline skills or knowledge. Students lacking the minimum requirements can be asked to leave (if appropriate), switched to an appropriate level class (if available) or told that they will not get any assistance regarding baseline information and they must refrain from asking it of their neighbors.

Why this is important: Students who are not adequately prepared for class prevent the prepared students from experiencing the maximum learning environment. And in some scenarios, a student lacking skills, knowledge or experience could place themselves, the other students, or the instructor at risk. Making one student who doesn’t belong in class unhappy is much better than disappointing the rest of the class.

Don’t reinforce bad behavior. The student that wants you to confirm every step (if not necessary) will continue to expect confirmation if the teacher complies with each request. The student who interrupts will continue to interrupt if the instructor allows it. Most adults (and kids for that matter) will stop negative behavior if they do not continue to receive some level of reinforcement from that behavior, and many times that reinforcement is actually coming from the instructor.

How this helps: Being aware that often our response is compounding the problem can help us stop the cycle before it starts. Most bad behavior is some form of seeking attention; stop giving attention and the behavior stops, too! In extreme cases, another inappropriate action will take its place, but the rule still applies.

In Part 3 of the series I will discuss what to do when your strong defense just isn’t enough and now you need some offensive tactics. Learn my secrets to regaining ownership of your class once you see it start to spin out of control. Have you tried any of these techniques for classroom management for adults in the past? Can you see how you might use one or more of these in the future? Do you have any questions on how to implement these tactics? I would love to read your thoughts, insights and questions in the comments below and I promise to respond!